When we realize a student does not understand a complex chunk of text, we may need to stop asking questions for understanding and “think aloud” for the student, modeling how to make sense of the text.

What follows is an excerpt from a middleweb.com column “Letting Go is Messy” that I co-wrote with Julie Webb (@LitCentric) highlighting key aspects of an effective teacher think aloud.

Why model strategic processing for the student?

There are a variety of reasons why a student may not be engaged in the strategic processing necessary to make sense of a source. Truthfully, we can never fully know what that student is thinking. We can only surmise from what they have shared with us (orally or in writing) and identify teaching points they may need. Chances are, if a student is not engaged in a type of strategic processing (during reading, writing, math, etc.), it is because they don’t know what they don’t know. They’ve never experienced that type of processing; they’ve never thought about making sense of a source or a problem in that way. When you model strategic processing for a student, you are creating an experience that can serve as an anchor for that student’s thinking, an experience they can draw on when they strategically process text on their own. This implies, though, that the student needs to be a fully engaged partner when you model. While you are modeling, they need to be observing closely, connecting to what they already know about making sense of a text and adding to what they can do to problem solve.

What should the “I DO” or “Modeling/Connecting” include?

There are three important parts of the modeling/connecting phase:

- A teacher-led explanation of the strategic processing that includes the WHAT and WHY as well as the HOW and WHEN (Almasi & Fullerton, 2012).

- A teacher “think aloud” that makes your strategic processing visible to the student (Cummins, 2019).

- Opportunities for the students to engage, bringing some of what they already know to the conversation (Gaffney & Jesson, 2019).

Before we share an example of what this looks like, take a moment to read this excerpt from the NEWSELA article “From turtles to whales, marine animals have the same moves”:

An international team of researchers published a new paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The scientists used tracking-device data to better understand the [animals’] motion in the ocean. They compared the daily movement patterns of thousands of animals across 50 different species. They found that even though some sea creatures are much bigger than others, many of them share the same basic choreography.

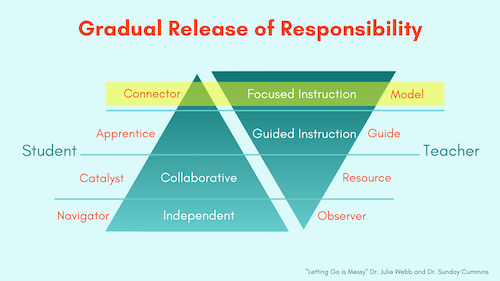

What follows is an example of how a teacher might model “determining what’s important while reading” during a conference with a student. (This could easily be adapted to a whole group mini-lesson.) Notice how in the beginning the teacher offers an invitation to engage in a partnership. Then the teacher moves into the What, the Why, and the How before thinking aloud using “I” statements. The When concludes the teacher’s modeling. Importantly, along the way, the teacher draws the student(s) into connecting and adding. The close includes an invitation to move into the next stage of the gradual release of responsibility or “WE DO.”

Sample Modeling-Connecting Partnership or “I DO”:

Teacher: It sounds like you have a general sense of what this article is about – how some ocean animals move in similar ways. Would it be okay if we looked together at the paragraph you just read and thought about what we are learning?

Student: [Nods.]

Teacher: [Explains WHAT.] Frequently, in articles like this, there is a LOT of information the author wants to share. It might feel overwhelming. Have you ever read a source and thought, “Oh this has a LOT of information?”

Student: Yes! That article we read about weather last week had a lot of information. I couldn’t remember it all!

Teacher: [Explains HOW.] Exactly. When I’m reading an article with a lot of information like this one, I try to remember what my purpose is. I think in this case, our purpose is to learn new information about research on ocean animals, to learn information we didn’t know before. Does that make sense? This helps me think about which details I need to think about more carefully. So while I’m reading, I’m going to be asking myself, “What is new information that seems kind of important to think about?”

Student: [Jots question “What is new information?” on a sticky note.]

Teacher: [Explains WHY.] If I notice and think about the details that are new to me, I can compare the details to what I already know. This will help me understand and remember what I read. This may also help me think about what’s important in the source.

I’m going to keep my purpose in mind – What is information that I didn’t know already? – and as I read, I’m going to notice and think through this new information.

Watch me do this. [Reads aloud the first sentence.] “An internationalteam of researchers published a new paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.” [Pauses to think aloud.] There’s a lot of information in this sentence that feels new to me. Just the first part, “international team of researchers,” is a mouthful, huh? I’m going to think about the meaning of this phrase. I notice the word “international” so I’m thinking that these people are from all over the world; the word “team” makes me think they are working together or collaborating. That’s pretty cool that a group of researchers from all over the world are working together, huh?

When I look at the next phrase, “published a new paper,” I think about what I know about getting writing published. It’s a lot of work to get published and you have to think that what you are sharing is very important for others to know about, maybe even new brilliant information that can change the world. Why else would you go to the trouble?

Looking at the last part – “in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.” I realize I have no idea what this is; I’ve never heard of this. Have you? What do you think this is?

Student: Maybe some kind of group. Maybe they do something with science because it has the word science in it?

Teacher: I was thinking that, too. We may not know for sure but we can draw a conclusion that this is some type of organization that publishes scientists’ work.

[Sums up learning.] So what have we learned from this one sentence? I’m thinking that this group of researchers has gotten together to share some very important information in a publication that reaches a large group of people who are interested in science. This makes me want to read the rest of the article to find out what they learned and why it’s so important. What about you? What are you thinking right now? [Alternatively, the teacher could start with “What did we just learn from this sentence?” supporting the student’s response by adding what the teacher learned as well.]

Student: I’m just wondering where the researchers are from and which animals they researched.

Teacher: Right? So thinking carefully about what we are learning from this sentence led us to ask more questions. That definitely makes me want to read on and I can use those questions as a purpose for reading, too.

[Sums up strategic processing, reviewing WHY.] So what did we just do as readers right here? We knew our purpose – to read for new information; we read a sentence and then reread that sentence thinking about the parts and what those parts mean. We also summarized our learning. I think tonight I’ll be able to go home and tell someone about what this group of researchers has done and if I keep reading like this, I’ll have a lot to say about that! [Alternatively, the teacher could start this part by asking, “In your own words, can you summarize what we just did to make sense of this complex sentence? And why is this important?” and supporting the student’s response as needed.]

[Explains WHEN.] When you are reading, make sure you keep your purpose for reading in mind. Think of that purpose as a question like, “What am I learning that is new information?” And when you feel like you come across information that helps you respond to that question, slow down and think through that information – maybe a chunk at a time like we did asking yourself, “What am I learning that I can remember and use to understand the source better?” You may not understand everything you read, but you’ll have a better understanding than before.

Want to try doing this together for the next few sentences?

Remembering the Why and When

In our reading conference example the teacher enacted focused instruction by acting as a model who invites the student into a teaching-learning partnership. The teacher taps into what she knows about her students and strategic processing with few assumptions, beginning by asking the student to share their best thinking. This serves as an entry point for focused instruction, with the teacher nurturing the partnership along the way with clear explanations of the What, Why, How, and When of this type of strategic processing.

Many teachers employ focused instruction with a strong sense of the What and How of a strategy, but sometimes neglect to explain Why the strategy matters and When learners can make best use of it to help them grow. These are critical steps in the teaching-learning partnership because they help us move toward the goal of fostering independent learners.

The last statement in the student-teacher discussion, “Want to try doing this together for the next few sentences?” is an invitation to continue the partnership, releasing some control of leading the learning to the student. We ultimately want our students to continue to learn on their own, without our guidance and support, and recognize opportunities to try this type of strategic processing on their own, applying it flexibly at points of need.

We recognize that work like this is never really over and that it’s certainly easier said than done. Teaching-learning partnerships can be challenging because we as teachers can’t always anticipate what students will say, do, or need in a learning opportunity. The best we can do is to balance being prepared for different scenarios while staying responsive and teaching in the moment. This becomes easier with intentional study and deliberate practice, but it’s almost certainly guaranteed to be a little messy and we’re okay with that.

If you’re interested in seeing more examples of teacher think alouds, there are many in my book Close Reading of Informational Sources.

Hope this helps.

S

References

Almasi, J. F., & Fullerton, Susan King. (2012). Teaching Strategic Processes in Reading. New York, Guilford Press.

Cummins, S. (2019). Close Reading of Informational Sources: Assessment-Driven Instruction in Grades 3-8. New York, Guilford Press.

Gaffney, J. S. & Jesson, R. (2019). We must know what they know (and so must they) for children to sustain learning and independence. In M. B. McVee, E. Ortlieb, J. Reichenberg, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), The Gradual Release of Responsibility in Literacy Research and Practice (pp. 23-36). Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing.