When I lean in for a reading conference with a student (who is reading an informational source), I always start by asking her to tell me a little bit about what she is learning from the source. I say, “Tell me what you learned in this section” or, in the case of narrative nonfiction, “What just happened in this section of the text?” When I do this, I’m checking for (mostly) literal understanding of what the student just read or, in Fountas & Pinnell terms, “within text understanding.”

As the student responds to “What did you just learn?”, I assess by asking myself questions like:

- Is the student talking about the content on the page in front of them?

- Are they able to describe what they’ve learned easily, in their own words?

- What are they leaving out that maybe they do not understand?

Sometimes a student will look at you and just say, “I don’t know.” That’s great. You can move into teaching from there.

But lately, I’ve been noticing some other ways students try to get by–

1) The student talks about something they already knew (or they learned in the preview)…versus what’s in the text.

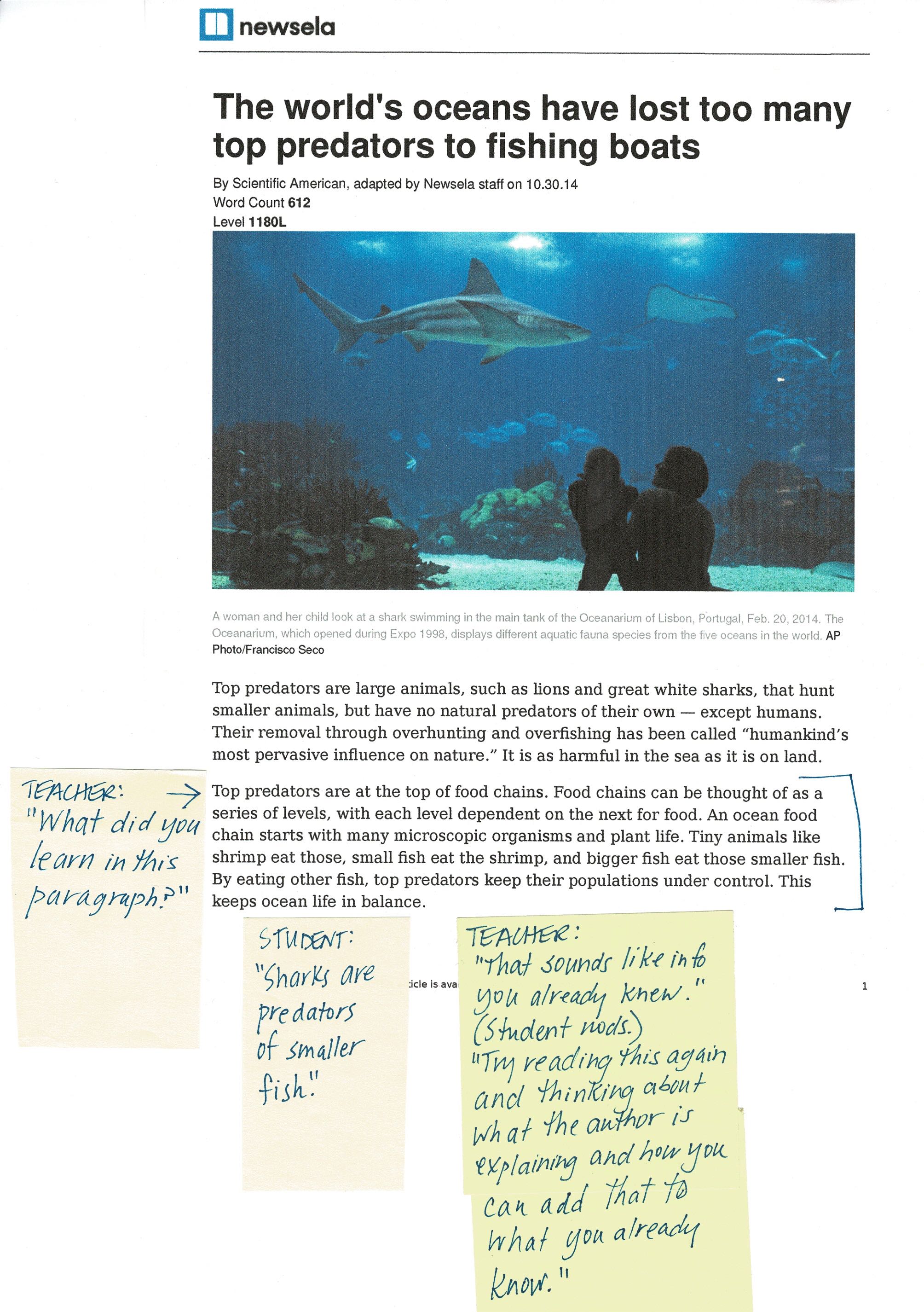

Example: A student was reading a NEWSELA article “Fishing boats are taking too many big hunting fish from the sea” (adapted from Scientific American). He’d just finished this paragraph:

Top predators are at the top of food chains. Food chains can be thought of as a series of levels, with each level dependent on the next for food. An ocean food chain starts with many plants and tiny animals like shrimp. Small fish eat those and bigger fish eat those smaller fish. Top predators help control the populations at lower levels. This keeps all the ocean life in balance.

When the teacher and I asked him to tell us a little bit about what he’d learned, he said, “Sharks are predators of smaller fish.” His comment did not reveal learning from this paragraph. He’d probably inferred that the author was going to move into talking about sharks, but he did not reveal his understanding of the content in this paragraph. When we probed further (“Tell us a little more”), he was not able describe how the author had described the concept of a food chain as a “series of levels,” etc. By listening carefully and probing, we determined we needed to support him (via a shared think aloud) in making sense of the content stated explicitly in that paragraph.

2) The student talks about an easier part of the text (or even an easier part of a sentence) and they DO NOT talk about the harder parts of the text (or the sentence) that they may not have understood.

Example: During a lesson with students reading an article about the future of drones, each time I leaned in and asked an individual to tell me about what she’d learned so far in the article, she referred to the statement in the article about drones delivering pizzas someday. None of them referred to the section of the article they’d read about first amendment privacy rights being violated by drones. When I probed further about what they’d learned from this section, I realized they did not understand it. Their response to my query, “What are you learning?” was “what I am understanding easily” (and maybe, in this case, “what did I find appealing” ;). So I moved to support the in understanding this harder content as part of our conference.

3) They repeat phrases or language from the text without a real understanding of what that language means or because they don’t know what it means.

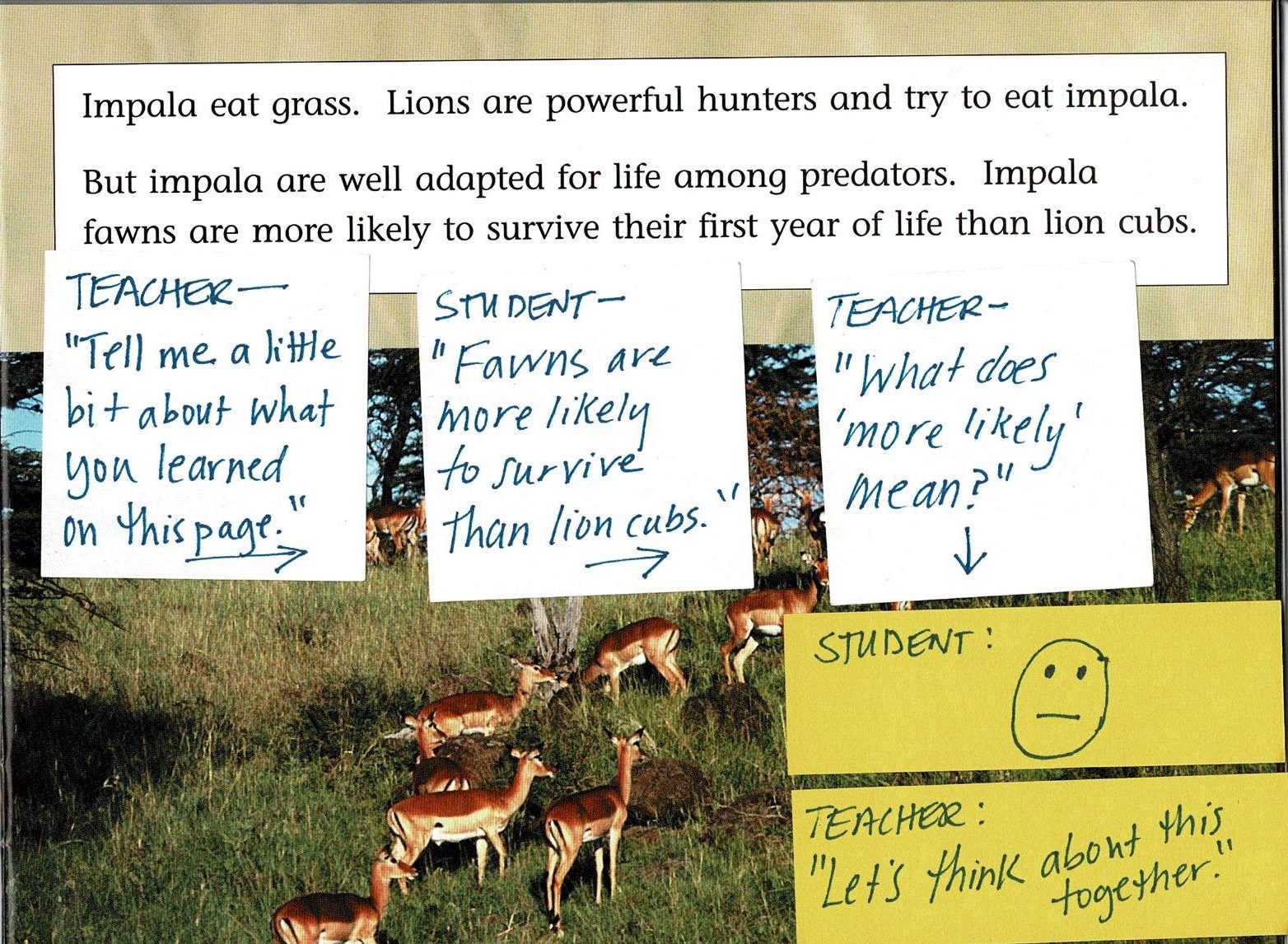

Example: A student had just read aloud the following sentences (to the teacher):

But impala are well adapted for life among predators. Impala fawns are more likely to survive their first year of life than lion cubs.

When we asked her to tell us what she’d just learned, she said, “Fawns are more likely to survive.” Sounds good, huh? Then we asked her “What does more likely mean?” No clue. So we knew where we needed to teach next.

What I’m also finding is that we (me included) are sometimes too quick to accept what students say. We are not giving ourselves a moment to assess and then think through how to respond in a way that has generative value.

A FEW SUGGESTIONS for ASSESSING (literal understanding) in the moment (or what I’m learning):

- Start with a general question or prompt like, “Tell me a little bit about what you’ve been reading or learning…”

- Gently cover the passage and ask the student to look at you as they talk. Then you are messaging that this is a conversation about their learning.

- LOOK AT THE TEXT FOR YOURSELF. Don’t be afraid, as the teacher, to look back at the text to compare what’s in the text to what the student has said. As I listen to the student, I lift my hand up just enough to glance at the text underneath as a way to help me check for understanding.

- When needed, PROBE-ASSESS FURTHER with statements or questions like:

- Tell me more.

- What does the phrase “more likely” mean?

ONCE YOU ASSESS THAT A STUDENT IS NOT UNDERSTANDING WHAT THEY READ (or maybe not monitoring for meaning), here are few suggestions:

- FOCUS ON ONE SENTENCE. Ask the student to read one sentence and then look up at you to talk about what he learned. (There can be a LOT of info in just a sentence or a paragraph.) If they are able to do this, point out to him how stopping and thinking about what you’ve just read is a helpful way to make sense of the details in a source and remember those details.

- THINK ALOUD FOR & WITH THE STUDENT. The temptation is to ask the student a bunch of questions like, “What does the lion do to protect her cubs?” and “Where does she take them?” and “What does she do while they are hiding?” and so forth. RESIST. These questions continue to assess comprehension but they don’t really teach students how to make sense of a piece of information. Instead think aloud as a though you are making sense of the information with statements like, “When I read this, I noticed the author was telling me where the mother lion takes the cubs–to a hiding place and I noticed a detail that tells me why–so the predators won’t find them while the mother is off feeding.” You might also need think aloud about how you used background knowledge or what you learned in another part of the source to help you make sense of a detail. Then you need to follow with, “What did you notice?” drawing the student into conversation with you about how we make sense of particular details in a source. (And conversations about how sometimes we can’t make sense but we have to try and then we just have to move on!)

- IF THERE’S A VOCABULARY ISSUE, LOOK TOGETHER FOR CONTEXT CLUES OR TEACH EXPLICITLY.

There’s so many ways a student’s meaning making may break down while reading an informational source. I can’t get it all into one blog entry, huh? Hope these take aways are a bit of help.

S