It’s frequently true. We have grand conversations about engaging nonfiction and then when our students write in response…well, the struggle is REAL.

Here are some approaches I’ve found helpful in grades 2-6 —

- provide a clear purpose for writing,

- respond to just a part of a text – an important part,

- plan for what they will write,

- engage students in shared writing of parts of a response (before they write on their own),

- confer at the point of need regarding meaning, structure, spelling.

Just a few thoughts on #1-3.

1) Provide a clear purpose for writing.

Students need an audience (other than you). As much as I can, I give them a purpose for writing like:

- What can you tell someone at home tonight about what you learned?

- Write a letter to your principal about what you learned about 3D printers and why our school should buy one?”

- Use what you learned in these two articles about the work of public officials to persuade someone (in a letter) that they should run for office.

- Write a thank you note to a member of your science project team. Refer to what you learned in this short book about how teams of STEM researchers worked together to develop the Mars rovers. …

- Write a note to a friend about what you learned about…in this text…that you think is important…

Even if an authentic purpose is not readily available, at least make sure that they have a clear, focused prompt like –

- How do the redwood trees protect themselves?

- How did the Jewish resistance subvert the Nazi’s attempts to…?

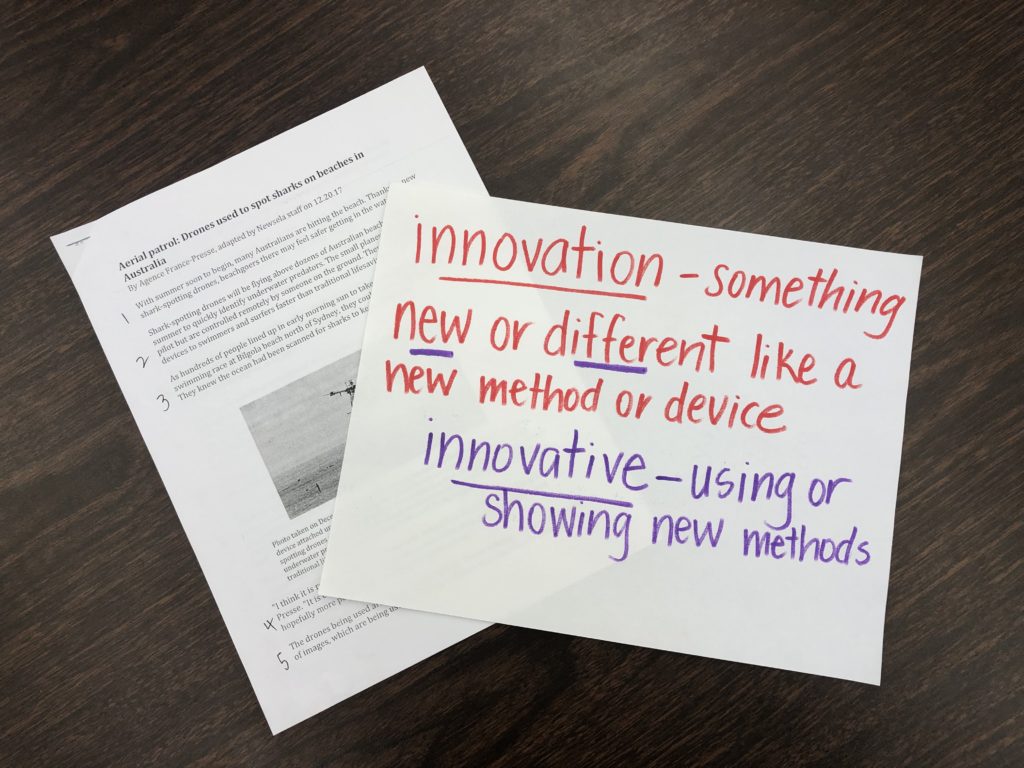

- What did you learn about innovative uses of drones? What makes these uses “innovative”?

2) Respond to just a part of a text — a section, a paragraph, a few sentences – that reveal a supporting key detail or a big idea.

Nonfiction can be dense with complex sentences. In just a few sentences, there can be several details worth noting, several details to support or reveal a big idea. Instead of asking students to write about an entire article (or book or video), ask them to write about one section (or short clip of) the source. (I’ve even asked students to write about what they learned in a single, but long, complex sentence.) If they are reading and responding independently, ask them to choose a particular section to respond to. Provide space and time to examine that section closely, read or view multiple times, annotate and talk about with others before they write. The more meaning they can make before writing, the more they will have to say in writing.

3) Help students plan for writing.

Ever have a grand conversation about a text and when the students go to write, they ask, “Now what do I write?” Or do your students meander, wander, lose their way after a great start?

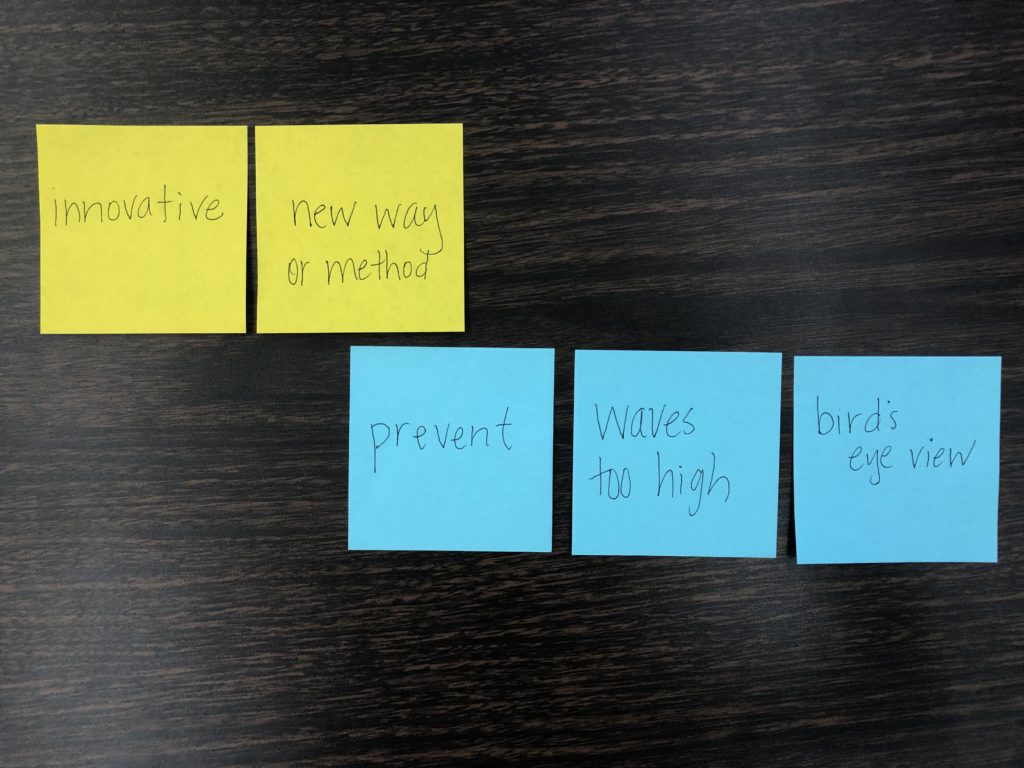

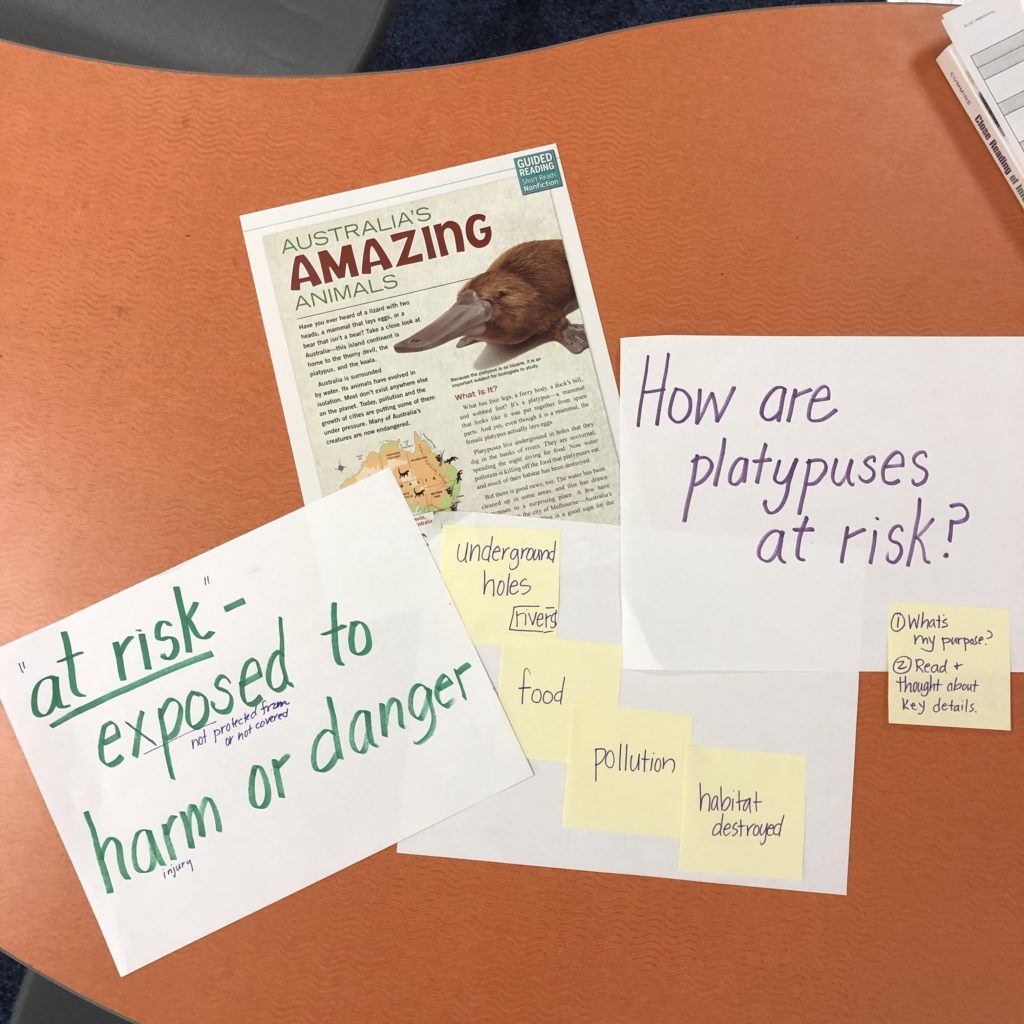

They need a plan for writing. This could be key words or an outline that serve as a guide. When you introduce students to how to plan what they will write about, you may want to be the scribe; in other words, engage students in shared writing of a plan. Below are examples of plans written during shared writing.

For the example above, the students read an article about the use of drones to detect sharks along Australian coastlines. The prompt for writing was – “describe to someone how drones are being used innovatively in Australia.” To help them generate the key words, I asked questions like, “How you introduce this topic to someone?” and “What would you say next?” and “After that?”

The key words on the yellow sticky notes—innovative & new way or method—were generated when we discussed how the students might begin their written responses. And then the key words on the blue sticky notes—prevent, waves too high, bird’s eye view—are key details the students chose to help them describe how the drones are being used.

For the key words above, similar to the students reading about drones, I helped the group of students identify key words that would help them answer the question, “How are platypuses at risk?”

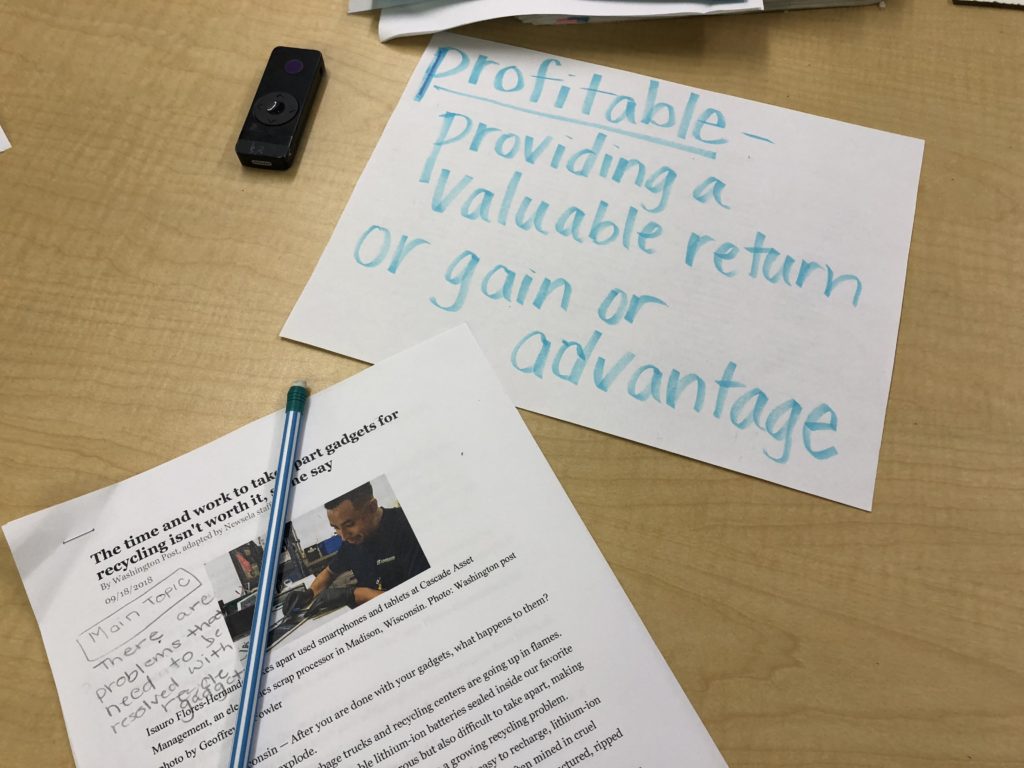

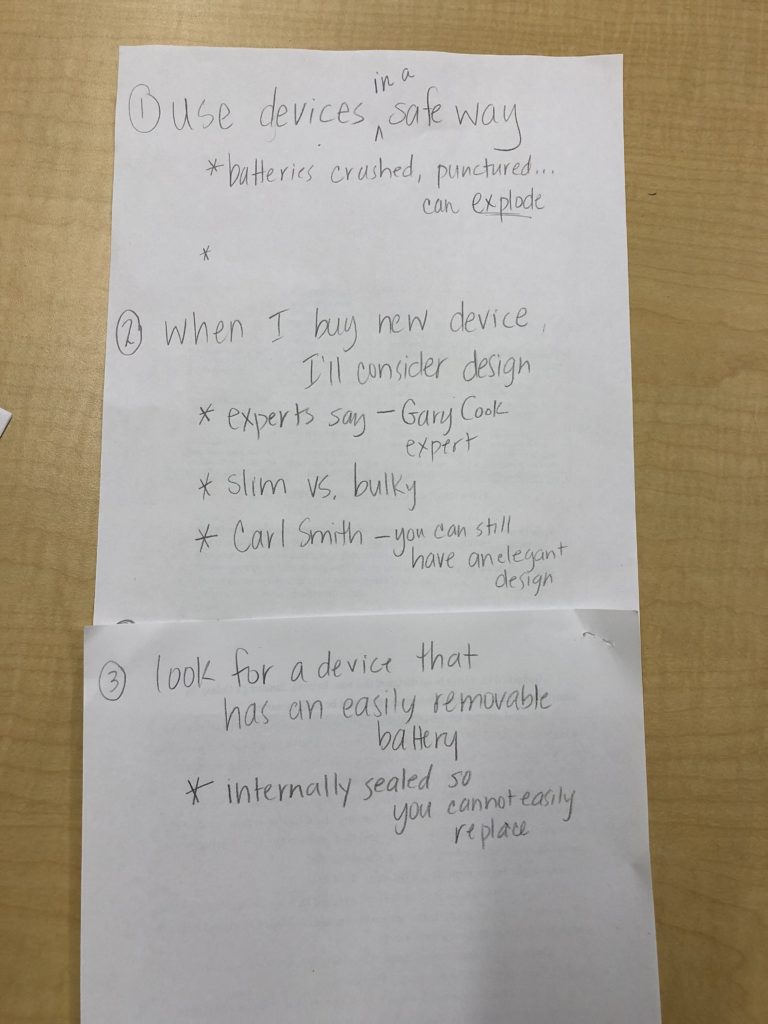

This group of students read an article about how hard smart devices are to recycle and the hazards they cause in landfills. Their prompt for writing was, “What did you learn from this article that you need to consider when you think about your own smart device?” (Everyone at the table had a device of some sort.) They generated key points they wanted to make in a response and located details in the text that supported their thinking. As they talked and looked back in the text, I helped them generate a shared outline with just enough details to help them remember but not so many that they could just copy in lieu of writing.

Hope these thoughts are helpful.

S

UPDATED 8/5/2025