Thoughtful, text-based predictions can make a big difference in students’ comprehension of complex informational sources. There’s a big difference between these two predictions: 1) It’s going to be about dolphins AND 2) The details in the heading, the intro and the photograph make me think this text going to be about the challenges that bottlenose dolphins face and what a group of scientists is doing to help them.

A few ways informed predictions are helpful:

- Predictions help you activate background knowledge.

- Predictions help you notice when an author has presented information you already knew.

- Predictions help you notice when new information is being presented. This may be an alert to slow down and pay attention.

- Predictions help you notice when contrasting information has been presented, information that may be wrong or that may need to be checked in additional sources.

What follows are some tips for teaching.

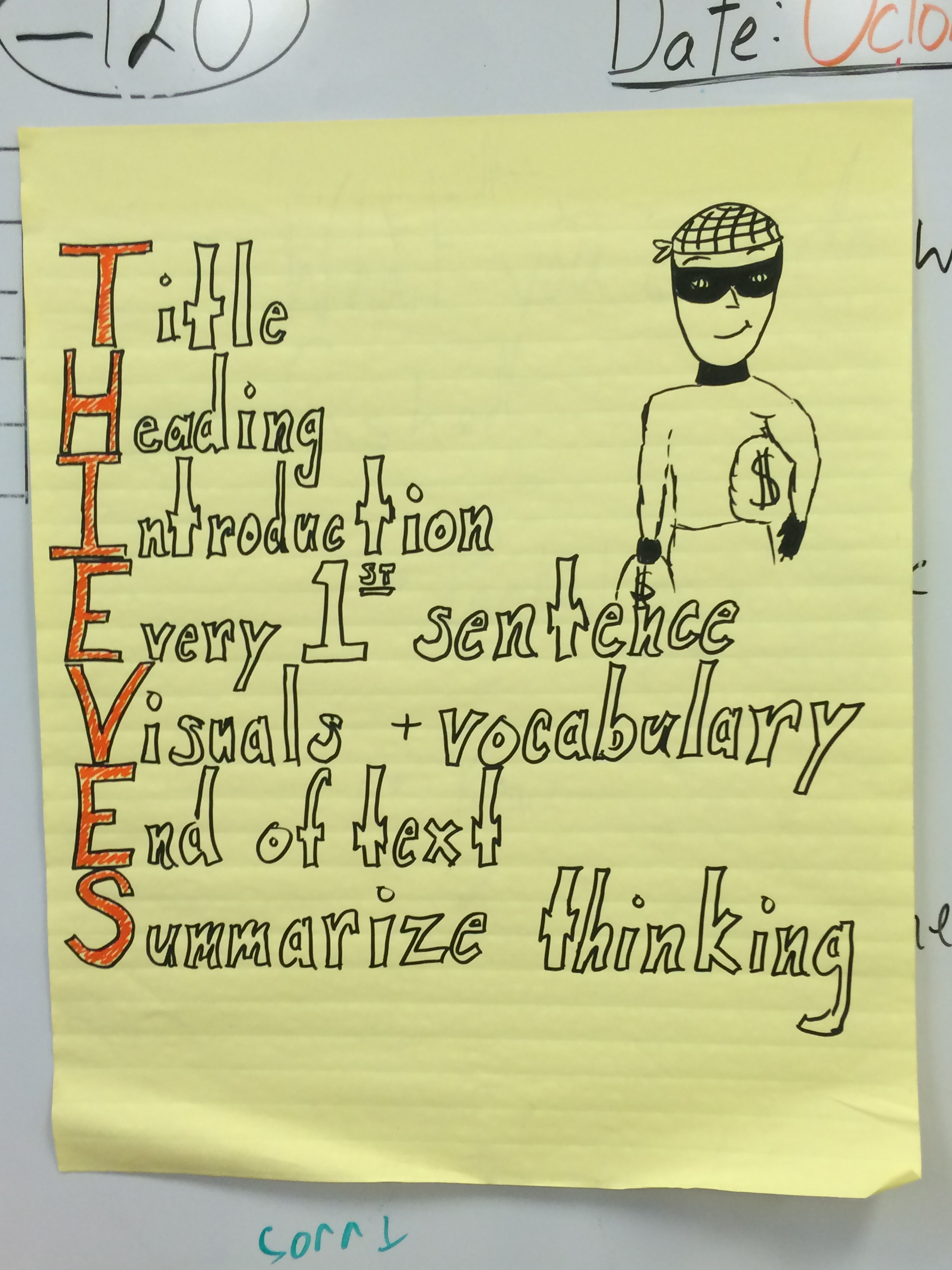

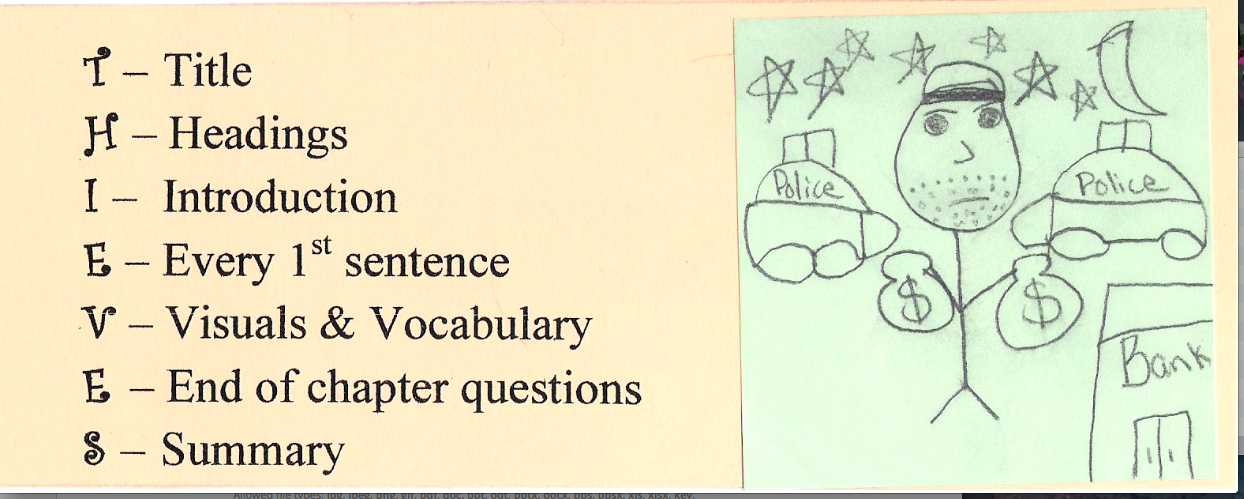

Choose a mnemonic like THIEVES, HIP or TELL.

Teaching students to use the mnemonic THIEVES (Manz, 2002) is an easy way to introduce making informed predictions. Being a “thief” in this case is not about stealing but about getting ahead of the author. The poster below (created by a colleague!) reveals the details of this strategy–students preview, predict & then summarize their predictions. Further down is a bookmark I created on tag board for students. The sticky note is one student’s interpretation of the word “thief.” If you don’t want to use the THIEVES mnemonics, there are plenty of other choices including HIP & TELL.

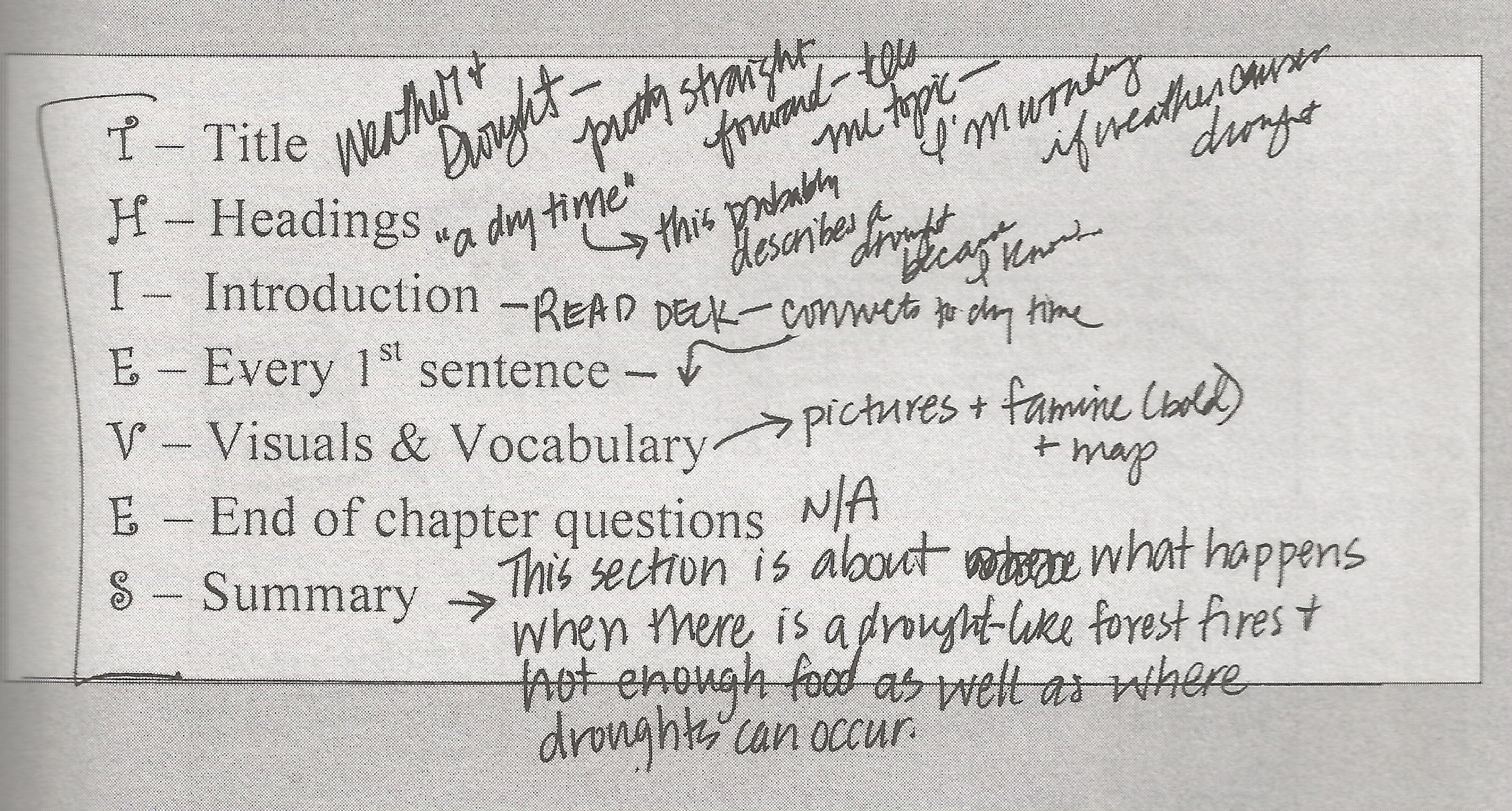

Be prepared to think aloud in front of students.

In advance of teaching lessons with THIEVES, I take notes in preparation for a think aloud. Below are my notes for a lesson with a text on droughts. When you think aloud in front of the students, post the source for all to view. Include in your think aloud what you noticed in a particular feature and how that helped you begin to think about what may be important in this article. For example, “I noticed that there’s a map indicating where alligators live and the decrease in their numbers due to…. I’m wondering if the author may be writing about the challenges alligators are facing.”

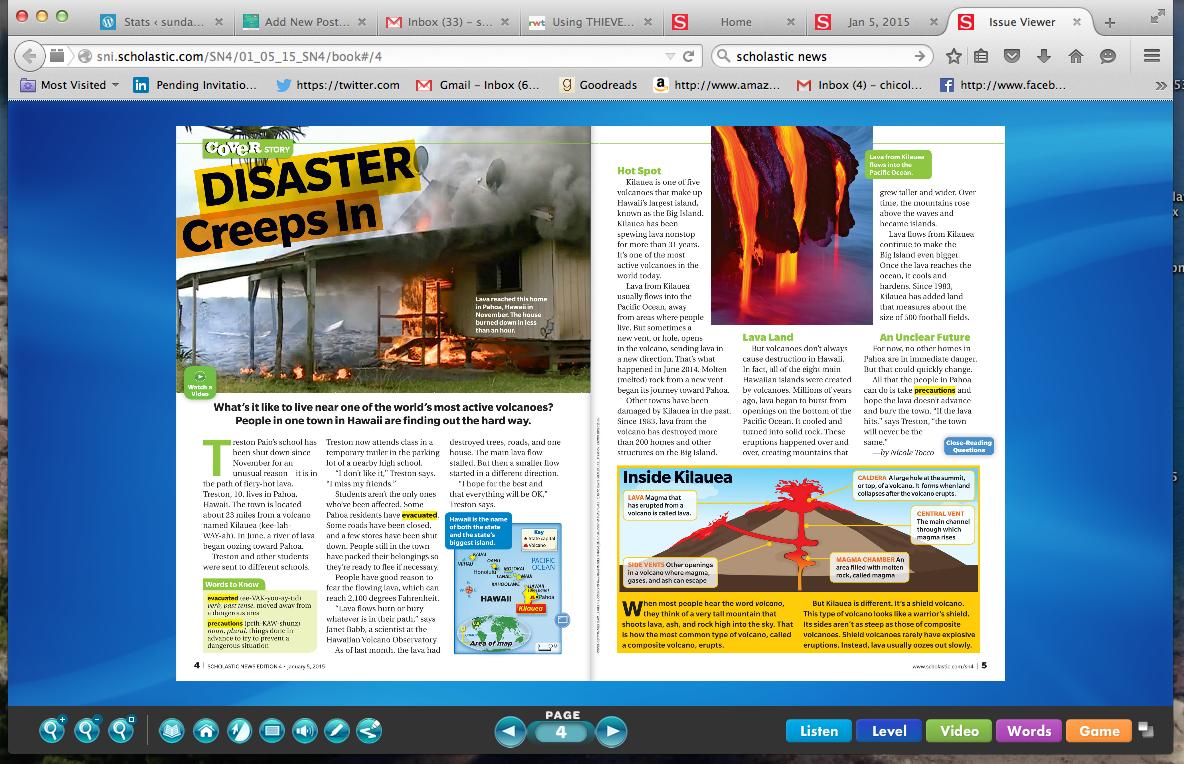

With feature dense sources, preview fewer features.

A two-page spread can have a LOT of information. Students might get overwhelmed previewing a whole article or book. Frequently there’s enough information early in the source that can help them make an informed prediction.

An example of a feature-dense text in Scholastic News.

Teach students to think flexibly as they use THIEVES.

Sources come in many formats. Sometimes there are headings, sometimes there are not. Sometimes just the headings a and a few visuals provide enough information to make a prediction. Teach students to consider the title, heading, intro and other features as choices for what they can preview to “get ahead.” See this blog entry on using THIEVES flexibly.

Ask students to reflect on their predictions.

Predictions are not about WRONG vs. RIGHT. They are about helping us, as readers, make sense of a text. Students may need to hear us say this. Build in time (after reading) to reflect on the value of their predictions.

We make predictions during reading, too.

Predictions don’t just happen before we read. We are always making predictions about what we’ll be reading next – based on what we just read, etc. Predictions help us monitor for meaning. Engage students in talking about and reflecting on how they do this.

In the newest edition of Close Reading of Informational Sources, I describe lessons with THIEVES and provide charts with tips on conferring during THIEVES lessons (p. 77), and assessing students’ use of THIEVES (p. 78-79).

Okay…hope this helps.

S

FIRST EDITION POSTED 9/5/2015

REVISED & UPDATED 9/15/2021